Initially, debt facilitated rapid economic expansion. Much of Asia's growth over the last five years was investment driven (Garnaut 1998). But it was invested in the non-traded goods sector. In the end, it was no different from other speculative investment bubbles. Thailand was hit first, triggered by a series of competitive devaluation started by the Chinese renminbi in 1994 (of about 35%), the yen-US$ rate in 1995/96 and that of the New Taiwanese dollar (Western 1998). (See figure 1 below)

Figure 1: Percentage change in the value of US$1 measured in East Asian currencies (Relative to the benchmark rates in September 1985) (Source: Institute of Developing Economics)

This strengthening of the US dollar against the yen and other Asian currencies generated a large nominal effective appreciation of currencies pegged to baskets with a high dollar weighting (ibid.). Together with high domestic demand and a slump in the international market for electronic products, they hastened a contraction in overall export growth in Thailand, Malaysia, South Korea and Indonesia.

After currency traders attacked the Thai baht in July 1997, one would ask why did the rupiah and won have to depreciate also (not to mention the ringgit and peso)? Garnaut (1998) uses the term 'contagion' to describe the rapid spread of financial instability through East Asia. According to Garnaut, the lesson learnt in Thailand that the perceived implicit guarantee of asset values by defending the pegged exchange rate has to eventually be abandoned, send shockwaves to other parts of Asia with the same institutional weaknesses. These fears and nervousness are especially felt by investors who had poor understanding of the workings of the economies in which they were exposed, and had been surprised by the dramatic falls in currency and asset values in Thailand. This caused a sudden and large increase in risk premium on investment throughout the region. These sources of contagion "contributed to the pressure on fixed exchange rates, and after the abandonment of established pegs, to large falls in currency values" (ibid. pg. 5).

The events in the second half of 1997 also revealed crippling weaknesses in regulatory systems and financial institutions in Thailand, Korea and Indonesia in particular. One feature of these institutions and other enterprises was that they were exposed to US dollar exchange risk, which saw their short-term dollar liabilities soared when their currencies devalued sharply. These uncovered dollar liabilities, if large enough, could bankrupt a business and caused institutions to be insolvent.

Remedies for the Economic Crisis

When talking about policies to overcome Asia's economic crisis, we have to look at different perspective. Knowing that Japan's recession was the cause and hindered the recovery process, we first examine what could be done in Japan.

With mounting bad debts and capitalisation problems existing in Japanese banks, the immediate solution is to cut the Gordian knot of domestic bad debt and begin its recovery. However, this requires political will. Fortunately, a banking reform Bill and a related Bill for the recapitalisation of weak but viable banks, are expected to be approved by the Japanese Parliament by the end of its current session on 16 October 1998 (Straits Times 1998b). Hopefully this will help Japan to get out of its 'liquidity trap', and get its economy moving again.

On the East Asian front, particularly Thailand, Indonesia and Korea, the IMF-supported financial sector restructuring not only deals with weak financial institutions, inadequate bank regulation and supervision, but also the complicated and non-transparent relations amongst governments, banks, and corporations (Fischer 1998), which are the heart of the economic crisis. This is a prerequisite for IMF to release the fund it pledged. Without tackling these structural and governance issues, market confidence will not return, and so are the much-needed capital to kick-start their economies. But measures aimed at the banking system may not be sufficient. For example, two-thirds of Indonesia's external debt was borrowed directly by corporations (Stiglitz 1998). Thus, there should be policies regulating corporate borrowing aboard as well.

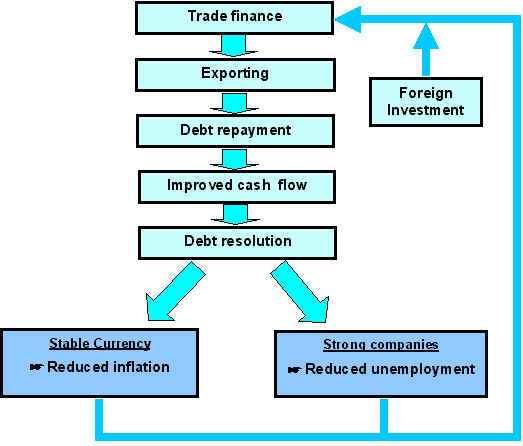

Appropriate monetary and fiscal policies also play an important part in the recovery process. According to IMF (1998), monetary policy must be firm enough to resist excessive currency depreciation, while fiscal policies will need to focus on reducing countries' reliance on external debts and take on the costs of restructuring and recapitalising the banking systems. Fiscal policies can also be exercise to reallocate resources from unproductive, non-traded goods sectors, to productive ones like the export sector. This is especially important to East Asia in jump-starting their economies, as the export sector has always been the most important hard currency earner, made much dearer with its current export price competitiveness. Policy-makers should restore trade finance by reinvesting these hard currencies into the export sector, and make debt repayment. Once the debt crisis is resolved, we would expect to see stability in exchange rates and stronger companies. This will help bring back investors, and further inject capital into the productive sector, and slowly move along the road to recovery. This process is illustrated below:

Figure 2: Restoration of trade finance to get out of the crisis (The steps involved)