CURTIN UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY

CURTIN BUSINESS SCHOOL

School of Economics and Finance

ECONOMIC THEORY 300

SEMESTER1, 1998

ASSIGNMENT 2

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1. INTRODUCTION

*

2. BASIC CONCEPT OF GAME THEORY

*

3. MAINTAINING COLLECTIVE ACTION - A ROLE FOR GOVERNMENT?

*

4. A BRIEF ANALYSIS INTO ARMS RACES

*

5. LIST OF REFERENCE

*

6. APPENDICES (News COVERAGE ON INDIA & PAKISTAN'S NUCLEAR TESTS)

*

1. INTRODUCTION

There was this story I read from a magazine few years ago which seems fictitious, but

it makes a profound point in the analysis of strategies:

A music conductor was on his way from Leningrad to Moscow by train. Two KGB agents who

had been watching his movements detained him while he was studying a musical score. They

reckoned that those funny musical notes in the score are secret coded messages and charged

him a spy. "Hey, those are notations from Tchaikovsky's Symphony No. 5!" he

insisted. "We've caught Tchaikovsky too, and he's already talking…now confess

and tell me about him!" yelled one KGB agent.

What should the conductor do? He knows the Soviet secret police's S.O.P.:

If he "confesses" and implicate his "collaborator", he will get off

with a year in prison while "Tchaikovsky", or whoever he may be, will get 20

years in Siberia! But if "Tchaikovsky" confesses while the conductor maintains

his innocence, the sentences will be reversed. However if both confess, each will get 10

years; or two years each if both maintain their innocence, as the KGB lacks confessions to

press charges.

This is prisoners' dilemma, and so are many players' who are involved in

strategic decision-makings! In the world of competition and survival, many organisations

(and individuals) are confronted with decisions that must take into account more

explicitly for the rival's likely responses. We can model this by a non-zero sum (and

often non-cooperative) game like the prisoners' dilemma.

This essay will illustrate the dominant strategy adopted by each player in a two-person

non-zero sum game, and outline the normative properties of the equilibrium and its

implications for the emergence of cooperative behaviour between economic agents. The role

of government as a mechanism for maintaining collective action will also be discussed. In

our discussion, I will draw on the problems of arms races to analyse using the prisoners'

dilemma.

2. BASIC

CONCEPT OF GAME THEORY

Game theory, as defined by Danben (1996), is a branch of mathematical analysis

developed to study decision-making in any situation involving a conflict of interest. In

such a "game", two or more decision-makers or "players" will select an

optimum strategy in the face of an opponent who has a strategy of his own, leading to a

desired outcome.

Game theorists have identified many types of games. In zero-sum games, the players have

exact opposite interests, thus the total amount won is exactly equal to the amount lost

(Danben 1996). In non-zero sum games, they have some interest in common. When the players

can agree on a plan of action, they are in a cooperative game. In a non-cooperative game,

the players cannot coordinate their choices. Coordination may be impossible if the players

cannot communicate, if no institution exists to enforce an agreement, or if coordination

is forbidden by law.

2.1 Prisoners'

Dilemma

In the scope of microeconomics, the most relevant game is the prisoners' dilemma. This

game provides some essential features of oligopoly market structure, and offers a good

illustration of how it leads to predictions about the behaviour of decision-makers in

competing for a larger share of profit amongst competitors. Similarly, in our analysis of

arms races amongst nations, the players would face the same dilemma of choosing the best

strategy taking into account the tactics adopted by its opponent.

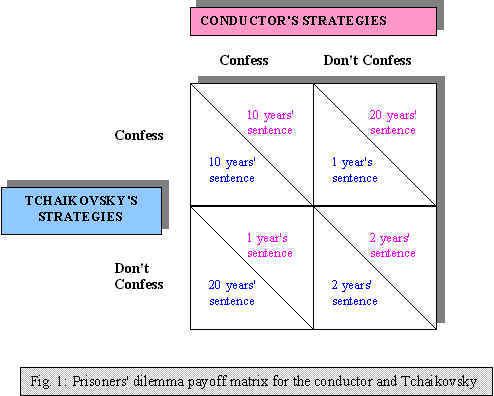

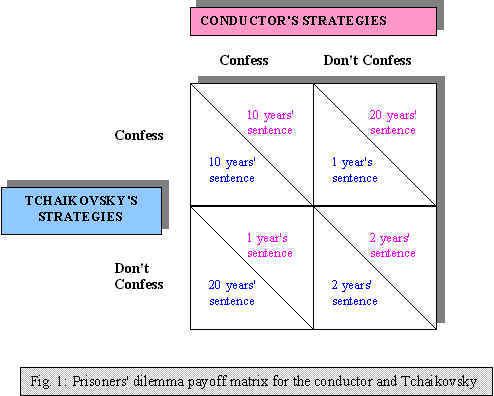

In the case of the poor conductor and "Tchaikovsky" illustrated earlier, we

can draw up a set of strategies and payoffs for both "prisoners" represented by

the payoff matrix overleaf:

The strategies in this case are: Confess or Don't confess. The payoffs (penalties

actually!) are the sentences served. How to solve this game? What strategies are

"rational" if both men want to minimise the time they spend in jail? The

conductor might reason this way:

"Two things can happen: Tchaikovsky can confess or keep quiet. Suppose Tchaikovsky

confesses, then I'll get 20 years if I don't confess, or 10 years if I do -- so in that

case it's best to confess. On the other hand, if he doesn't confess, I'll get 2 years if I

don't either, but in that case, if I confess I'll get only a year! Either way, it's best

if I confess…"

But Tchaikovsky can, and presumably will reason in the same way -- so they both confess

and go to the prison for 10 years each. Yet, if they had acted "irrationally"

maintaining their innocence, they could have gotten off with 2 years each. In this game,

to confess is a dominant strategy and when both prisoners confess, that is the dominant

strategy equilibrium and also a Nash equilibrium (at quadrant I).

2.2 Normative Properties of Dominant

Strategy Equilibrium

The prisoners' dilemma illustrates how self-interest may lead to a world of

non-cooperation. Here we assume that there is no communication between the two

"prisoners". However, if they could communicate and commit themselves to

coordinated strategies, they are unlikely to fall into quadrant I but end up in quadrant

IV where both are better off.

If this game is played repeatedly, players are also more likely to arrive at some form

of cooperation after developing their reputations about their behaviour, and studying the

behaviour of their opponents. One strategy that worked best is "tit-for-tat",

which means that what each player should do this round depends on what the other players

did on the previous round. According to McTaggart, Findlay & Parkin (1996, p. 315), a

trigger strategy may occurs as the other extreme end of punishment indicating there are

"other intermediate degree of punishment". One example could happen if one

player cheats on one period, the other player could punish by refusing to cooperate for a

certain number of periods.

The more important feature of the DSE (or the Nash equilibrium for that matter) is that

the outcome (or payoffs) is not what the players would unanimously wish for. This

remarkable result -- that individual rational action results in both players being made

worst off in terms of their own self interested purposes -- is what has made the wide

impact in modern social and political science.

It should be noted, however, that DSE (as well as Nash equilibrium) may be unique,

exist in multiple (ie. more than one DSE), or does not exist at all.

2.3 Implications for the

Emergence of Cooperative Behaviour

We have discussed how a possible cooperation between players of a prisoners'

dilemma game will lead to a Pareto efficient outcome. But is this outcome socially

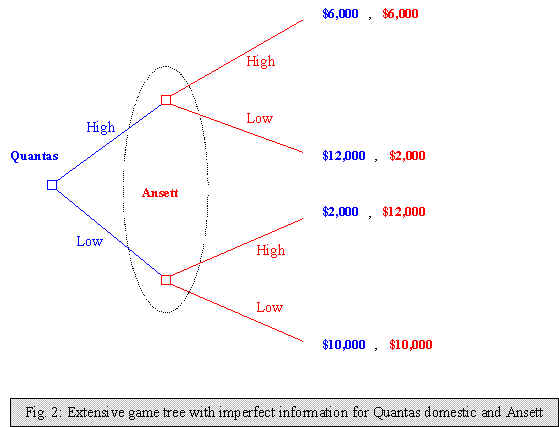

optimal? To give a better picture, let's reinterpret the above prisoners' dilemma game to

one of the business world. Assuming 2 rival airline companies -- Quantas domestic &

Ansett, fighting for a bigger market share for domestic air routes between Perth and

Melbourne or Sydney. The variables in this game is the output choice (ie. the number of

seats) manipulated by the price setting, ie., setting a higher price for the airfare

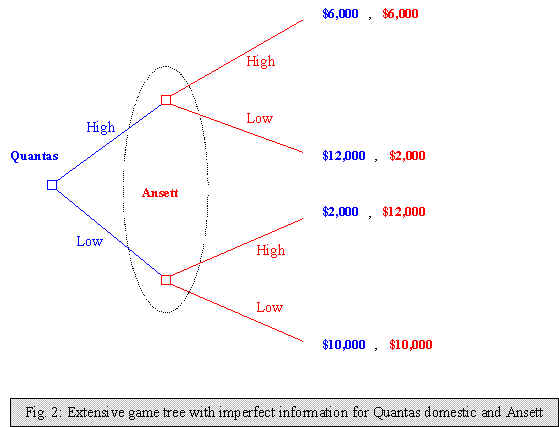

results in a lower output, and vice versa. If we represent this game in an extensive form,

we have the decision tree below:

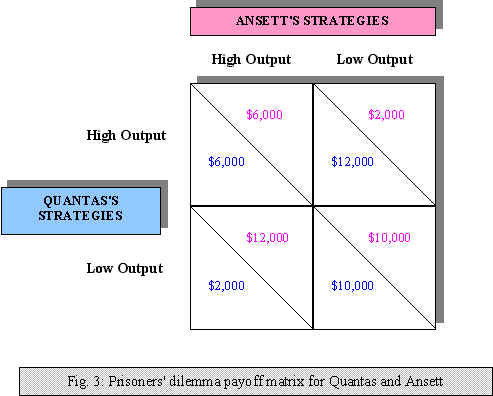

Here, we assume that both airlines have imperfect information, illustrated by Ansett

ignorance about which decision node it was in before making its move. If both airlines

were to adopt their dominant strategy, the dominant strategy equilibrium would be for both

to choose high output (competing with lower prices to undercut each other) and earn $6,000

each.

However, this DSE is Pareto inefficient, as both could be better off if they cooperate

and both produce low output (by raising their prices simultaneously) to rip off a higher

profit from consumers (making $10,000 each). Although this cartel-like behaviour could

lead to Pareto efficient outcomes for both airlines, these outcomes are not social

optimal. This is due to the fact that these firm-desired outcomes are achieved by firms

fixing prices above marginal cost and restricting output to achieve full cartel outcome,

which is not socially desirable.

It should be noted that even this price fixing practice is legal, there is an incentive

to cheat which would limit the participants from achieving the full cartel outcome.

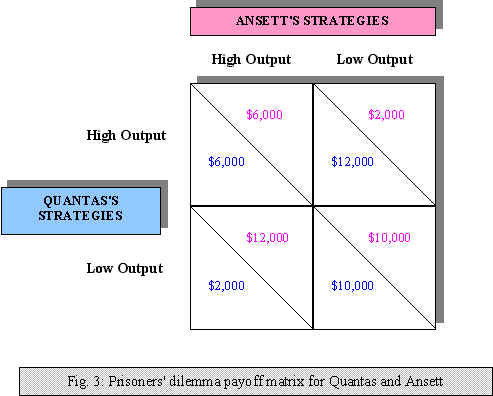

Referring to the normal form of the above game illustrated below, either airline has the

incentive to adopt high output, and if the other remains at agreed-upon level of output

(producing low in this case). The cheating firm will earn $12,000 while the other gets

only $2,000. However if both firms cheat, the collusion will breakdown with both firms

reverting to their dominant strategy of producing high and earning $6,000 each (quadrant

I).

3. MAINTAINING

COLLECTIVE ACTION - A ROLE FOR

GOVERNMENT?

3.1 Problems Associated with Market Failures

As illustrated in the previous section, if firms collude and form cartels to fix price

and limit output, it is not social optimal. By doing so, Katz & Rosen (1994, p. 420)

pointed out that the necessary condition for Pareto efficiency is violated, and thus the

First Fundamental Theorem of Welfare Economics does not hold.

The First Welfare Theorem states that "a competitive economy with a market for

every commodity generates a Pareto-efficient allocation of resources without any

government intervention [emphasis added]" (Katz & Rosen 1994, p. 421). But in

reality, the required competitive environment does not always exist: monopolies, cartels,

and to a lesser extend, oligopolies and other market structures that have a certain degree

of market power can cause market failure.

The role of government to correct market failure is thus to enhance efficiency. The

government could do this by breaking monopolies and outlaw formation of cartels in order

to limit market power and restore a social optimal outcome.

In America, the Antitrust laws was enacted with the primary objective "to promote

a competitive economy by prohibiting actions that restrain, or are likely to restrain,

competition, and by restricting the forms of market structure that are allowable"

(Pindyck & Rubinfeld 1989, p. 363); while in Australia, the Trade Practices Commission

act against certain restrictive practices (such as collusive pricing and retail price

maintenance, through the Trade Practices Act, 1974) but it does not assume that market

concentration necessarily means market power and behaviour contrary to consumer interests

(Samuelson et al 1992, p. 326-27).

3.2 Problems Associated with Collective Action

On the other hand, Hardin (1971) have shown using a n-person prisoners' dilemma that

collective action of large number of players in contributing toward the purchase of

the group collective interest would fail with each player defecting from contribution and

played the dominant strategy in a "distrust" environment.

In this case, the government can play a role in ensuring all players contribute toward

the objectives by imposing "sanctions" or providing private benefits to

participating members in the form of "injunctive proscription, prescriptions, or

fines and subsidies" (Ordeshook 1986, p. 224) as proposed by Olsen (1968).

The government's environmental protection policies that imposed fine to those found

polluting the environment is one example of government's effort to maintain collective

action.

4. A BRIEF ANALYSIS INTO ARMS RACES

Anderton (1986, p. 9) defines an arms race to be "a situation where two or more

parties change the quantity or quality of their armed forces in response to perceived

past, current or anticipated future increases in the quantity or quality of armed forces

of the other party(ies)". This definition includes situations where each nation

reacts positively to the other and in particular increases its military expenditures when

the other does. According to Isard (1988), each may do so in order to:

- reduce insecurity (reflecting a balance of power motivation);

- retaliate for the insecurity caused by the other's increased military expenditures and

military activities (reflecting a balance of terror motivation);

- counteract the ambition of the other; and/or

- be in a position of greater strength when negotiations on arms control are expected in

the future.

In our analysis, we shall focus on the recent stand-off between the Indian and Pakistan

government caused by their nuclear testing programmes.

4.1 Modelling

the Nuclear Arms Race in the Indian sub-continent

India has fought three wars with Pakistan since 1947 and suffered a crushing defeat at

the hands of China in a 1962 border conflict. The following year, it denied an allegation

by the U.S. that it produces an atomic bomb to counter China, which was expected to become

a nuclear power. It was only after Pakistan's commenced its alleged clandestine nuclear

weapons program in 1972 that India took the unavoidable counter-measure of

conducting its first nuclear test in Pokhran, in 1974 (Kapur & Wilson 1996; Moshaver

1991).

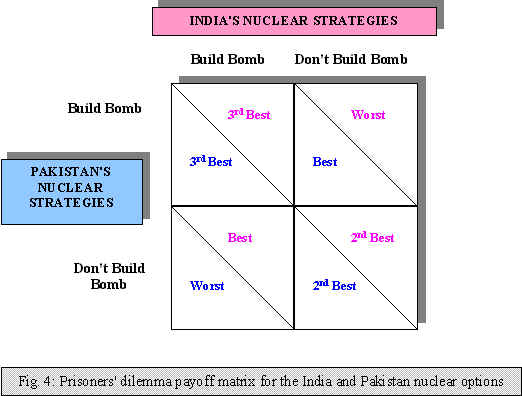

Before those developments, the dilemma then facing both would-be nuclear nations were

whether to engage in the development of nuclear weapons or not: a classic gun verses

butter issue.

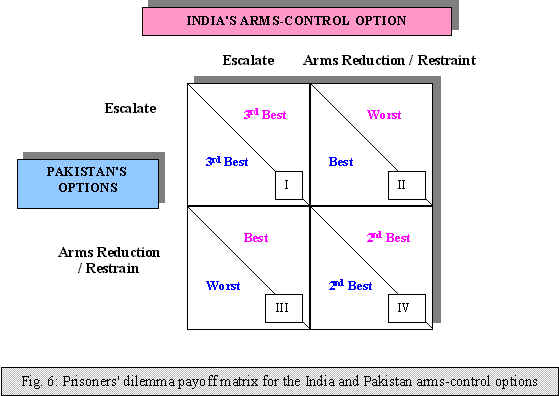

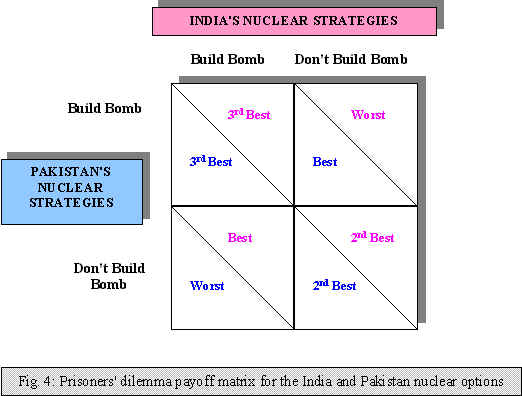

We can model this vaguely in a prisoners' dilemma payoff matrix overleaf:

Here, both nations identified the advantage of possessing nuclear weapons if the other

does not. Both nations, being non-signatories of the nuclear Non-Proliferation or other

related treaty, cannot rely on each other's assurance to stay in quadrant IV, where both

"don't build bomb" and concentrate on their economic development, deemed second

best option for both. Consequently, they ended up in the DSE.

"If India openly starts a weapons programme, the deep-rooted Pakistani fears of

India…would put tremendous pressure on Pakistan to take appropriate measures to avoid

a nuclear Munich at India's hands in the event of an actual conflict, which many

Pakistanis think very real."

Senior Pakistani nuclear scientist,

Abdul Qadir Khan, Fall 1985

"If Pakistan gets a nuclear weapon, India will have to think very seriously about

its own option. …We have every indication and information that leads us to believe

that Pakistan has not given up its nuclear weapons program and is bent on having it."

The late Indian Prime Minister,

Rajiv Gandhi, April 1986

The second Indian nuclear test of 5 atomic devices 24 years later on the 11 and 13 May

1998 came after the fact that Pakistan has not only acquired nuclear weapons and missile

capability, but also her Prime Minister threatened their use against India (Asiaweek

1998).

Then came the dramatic announcement of Pakistan's first-ever nuclear tests on 29 May

followed by another one the following day bringing a total of six devices exploded. This

matches India's total since 1974.

''Today we have successfully carried out five tests...we have evened the account

with India"

''We did not force Pakistan into this. In fact, it is Pakistan's clandestine

preparations forced us to the path of nuclear deterrence"

Indian Prime Minister

Atal Bihari Vajpayee, 29 May 1998

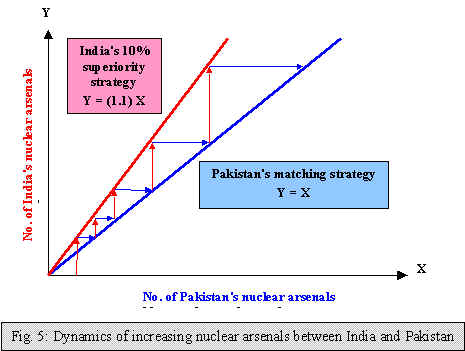

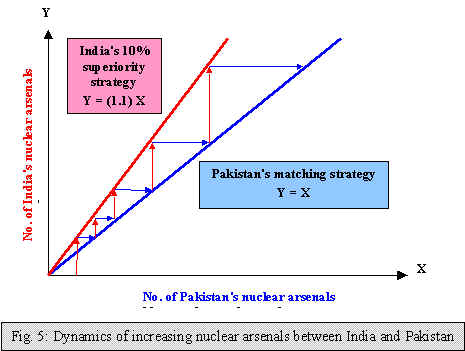

The 6 nuclear devices detonated by Pakistan portrayed Pakistan's desire to match

India's nuclear capabilities at least in quantity. If we assume that India wanted to lead

Pakistan in terms of the number of nuclear arsenal by, say 10% as her national security

policy, we can represent the dynamics of this nuclear weapons build-up in the diagram

below:

The vertical red arrows show India's increment of its nuclear weapons to keep up her

national security policy of 10% superiority over her rival; while the horizontal blue

arrows show Pakistan's desire to match India's number every round. This can leads to an

endless arms race.

"As a responsible nation, whose record of restraint and responsibility is

impeccable, Pakistan today assures the international community and, in particular, India,

of our willingness to enter into immediate discussions to address all matters of peace and

security, including urgent measures to prevent the dangers of nuclear conflagration"

Pakistani Foreign Secretary,

Shamshad Ahmad, 30 May 1998

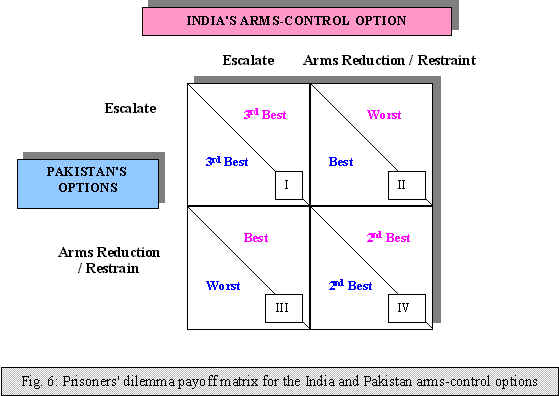

With the latest indication by India and Pakistan to go to the negotiation table, we

would expect to see some form of arms control. Again, we can model this situation below:

If both nations can work together closely to abide by the arms control agreement

(without attempting to cheat), we can expect to see a peaceful solution to the tension in

the Indian subcontinent with both India and Pakistan refraining from escalating the

nuclear arms race.

Although game theory can be (and have been) used to analyse political and military

events, they have been criticised as a dehumanising and potentially dangerous

oversimplification of necessarily complicating factors (Dauben 1996) which would lead to

deficiency in their analysis.

No. of words: 2496 (Contents Only)

5. LIST OF REFERENCE

Anderton, Charles H. (1986) 'Arms Race Modelling: Systematic Analysis and Synthesis',

Ph.D. dissertion, Cornell University.

Asiaweek (1998) 'Why India's Bomb is Justified' Asiaweek Online, Accessed on 24

May 1998 at [http://www.pathfinder.com/asiaweek/current/issue/nat3.html]

Axelod, Robert (1984) The Evolution of Cooperation, Basic Books, New York.

Danben, Joseph Warrant (1996) 'Game Theory', in Microsoft ® Encarta ® 97

Encyclopedia, Microsoft Corporation.

Hagenmayer, J., and Glazer, A. (1992) 'Albert W. Tucker, 89, Framed Mathematician', Philadelphia

Inquirer, 2 Feb, p. B7.

Hardin, R. (1971) "Collective Action as an Agreeable n-Person Prisoners' Dilemma',

Behavioural Science, 16. p. 472-81.

Isard, Walter (1988) Arms Races, Arms Control, and Conflict Analysis, Cambridge

University Press, New York.

Kapur, Ashok (1996) Foreign Policies of India and her Neighbours, St. Martin's

Press, Inc., New York.

Katz, Michael L. and Rosen, Harvey S. (1994) Microeconomics, 2nd Ed.,

Richard D. Irwin, Inc., Illinois.

McTaggart, D., Findlay, C., and Parkin, M (1996) Microeconomics, 2nd

Ed., Addison-Westley Publishing Co., Sydney.

Moshaver, Ziba (1991) Nuclear Weapons Proliferation in the Indian Subcontinent,

MacMillian Academic and Professional Ltd., Hampshire

Olsen, M. (1968) the Logic of Collective Action, Harvard University Press.

Ordeshook, P.C. (1986) Game Theory and Political Theory: An Introduction,

Cambridge University Press.

Pindyck, R.S., and Rubinfeld, D.L. (1992) 'Market Power: Monopoly and Monopsony' in Microeconomics,

2nd Ed., MacMillian Publishing Co., New York.

APPENDICES (News Coverage on

India & Pakistan's Nuclear Tests)

Sources :

- Straits Times Interactive [http://www.asia1.com.sg/straitstimes/]

- The Times of India Online [http://www.timesofindia.com/today/]

- The News Pakistan [http://www.jang-group.com/thenews]

- Asiaweek Online ;www.pathfinder.com/asiaweek/current/issue]

Return to Assignments for Semester 1, 1998