Recently, a great deal of attention has been paid in economics literature to convergence, or the tendency for poorer countries to grow faster than (and eventually catching up with) richer ones, and hence, for their levels of income to converge.

In modelling economic growth for this analysis, economists have identified two broad interpretations of the relationship between accumulation and output growth, the neoclassical view and the endogenous growth approach.

The neoclassical view, represented by works of Robert Solow, emphasises capital accumulation and exogenous rates of change in population and technical progress. It assumes that as physical (and human) capital are accumulated, their incremental contribution to output experience diminishing return. If this is the case, poor economies (those with smaller endowments of physical and human capital per worker) will grow faster than rich economies for the same level of investment in physical and human assets (World Bank 1993, p. 49), leading to the development of convergence hypothesis.

On the other hand, the new growth theory since advocated by Paul Romer generally does not prophesy that output per capita will eventually converge across all economies.

This assignment shall attempt to examine in greater details the differences between old and new growth theory especially their implications for convergence of level of per capita income across economies. In addition, the factors that promote convergence as well as their opposite forces shall be discussed.

Does the world take determinants of technology progress and growth exogenously? We shall first look at the principles behind the neoclassical model.

2.1 Theoretical Factors that Influence the Income Level

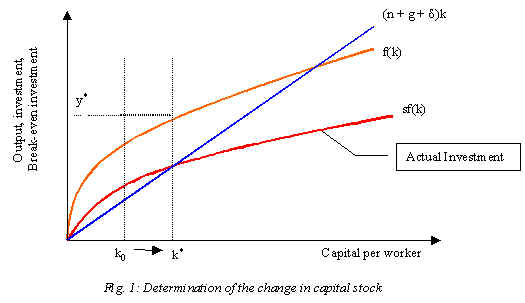

In a simple Solow growth model where economy produce a single output, it exhibits constant return to scale in production and diminishing marginal returns in the two factors of production, effective labour and physical capital. Increasing the capital to effective labour ratio means increasing the amount of capital per worker, thus increasing productivity and per capita incomes but at a decreasing rate because of the law of diminishing return. The savings rate and the population growth determine the rate of investment and the labour force growth rate, both exogenous to the model. By increasing the rate of investment beyond the rate of population growth, the capital to labour ratio would be increased and growth will occur but only during the transition phase until the steady state (k*) is reached (where all economic variables grow at the same rate). This process can be represented by the figure below:

Algebraically, the rate of change of capital to labour ratio with respect to time is given by the equation:

![]() (Romer, 1996, p. 13)

(Romer, 1996, p. 13)

The term sf ( k(t)) is the amount of investment per unit of effective labour, and the term (n + g + d ) k(t) is the break-even investment per worker needed to maintain the capital to labour ratio, k = K/L. When k is below (above) k*, actual investment per worker exceeds (falls short) that required to keep k constant, so k rises (falls). Thus the economy drifts toward k*.

In the Solow growth model where technological progress is exogenous, income will rise with the level of physical or human capital but the rise will not generate ever increasing growth rate. As Gould & Ruffin (1993) illustrates, skill workers increase the level of income just like any other productive factor, but they do not increase growth in the long run because technological progress does not depend on the presence of a skilled work force. They summed up by concluding that the rate of growth of an economy in the long run "simply equals the rate of growth in the labour force plus the rate of exogenously determined technological progress".

If the neoclassical model is relevant in the real world, empirically it should support a number of hypotheses. Firstly, it predicts that the growth rates of various countries will ultimately converge. In a free market environment, each country will have access to similar technologies and mobile factors of production will be drawn to areas where they are able to earn the highest rate of return. Poorer countries (given their initial position) are in a better position to exploit the gains from more capital since they have a relatively low capital to labour ratio. Given the usual neoclassical assumptions, countries with less capital will have higher returns to this capital and any investment capital will exhibit higher marginal returns. Thus, income convergence should occur over time as the increase in the capital stock takes hold in low capital regions.

Secondly, countries with high rates of population growth should exhibit slower per capita GDP growth as the capital stock, after spreading out among larger number of people will decrease the k. Thirdly, increasing the rate of investment will increase the stock of capital and therefore capital deepening will occur, resulting in higher growth rates.

2.2 The Empirical Evidence of Convergences

The convergence in per capita GDP between countries, as predicted by the old growth theory, has failed to materialise on a truly global scale. If income levels of countries tend to converge, poor countries should grow faster than richer ones as they catch up to reach the higher level of income. As Barro (1991) have shown using data from Summers & Heston (1988) international comparison project, there does not appear to be any strong negative relationship between per capita growth rates and the starting level of income (per capita), which may indicate that convergence is not taking place. However, if we examine the relationship again but this time holding the human capital constant, we find that the poor countries appear to be catching up with the rich countries.

Population Growth

In the old growth theory, increasing the capital to labour ratio is what leads to growth. Thus, increasing the population results in a decrease in k which leads to lower per capita income growth. Brander and Dowrick (1991, p. 815) have shown that decline in fertility (presumably highly correlated with the population growth rate) precede income growth in their sample of countries.

Investment in Physical Capital

As discussed, the traditional growth theory holds that capital deepening will lead to growth. Increasing investments leads to an increased stock of capital, which increases the productivity of labour, thus leading to economic growth. De Long and Summer (1991) find that investment in equipment is strongly associated with growth. They explain that new technologies have tended to be embodied in new types of machines.